Barbara Harris did not want to be interviewed…

Remembering Barbara Harris

I spent four days in Scottsdale, Arizona with the legend if not the pioneer in more ways than one, and it would turn out that Barbara Harris was, literally, the one who was more than one, famously. She could become someone else, apparently.

“This is not Daniel Day-Lewis,” playwright Arthur Kopit said, “this is Barbara Harris. She’s not becoming the role…she’s becoming someone else.”

“A battalion of Barbaras,” I read in an article about her and her title role in the totally unusual musical On a Clear Day You Can See Forever. “She’s a lot of different people,” Herb Gardner said, “quiet, loud, friendly, cold, totally competent, insecure…she’s like flip cards.”

I was intrigued by that.

Flipping through her press clippings at Lincoln Center Archives… it was sort of a page-turner. The press didn’t seem to know what to do with her. One journalist wrote that she could almost embody different ages. He couldn’t quite put his finger on it. She seemed to possess a womanly intuitiveness, the angst of a teenager, and the baby charm that made people pinch cheeks.

She had a mutable quality, I thought, and it appeared to be rather innate.

When The Second City arrived in New York in 1961, she wowed the crowd by “dishing out mad characters as if they were Christmas cookies.” Richard Rodgers, as in Rodgers and Hammerstein, was in the audience one evening, and she evidently left a lasting impression on him.

Rodgers had just teamed up with Alan Jay Lerner, another giant in the field of the American musical because they had lost their respective partners. A few months later, he brought Lerner downtown to see her perform in the kooky smash hit, Oh Dad, Poor Dad, Mama’s Hung You in the Closet and I’m Feeling so Sad. He suggested that they write their first musical together around her, so he brought Lerner downtown to see Barbara Harris perform in Oh Dad. They hired her on the spot, there.

According to Charlie Rice, a journalist, what happened to Barbara Harris in the span of six months was “unheard of.”

“It wasn’t like making a hole in one, it was like making a hole in none.”

No one even knew if she could sing — could she?

She didn’t seem to know, which was funny…perplexing…the press looking at one another— what? What do you mean? You’ve never really been a singer? You’re inspiring one of the most important musical collaborations in recent history. I had to laugh. Rodgers was tight-lipped and so was Lerner. Sort of delightful, baffling. And it seemed to be her fundamental approach in life. “I don’t know.” She had even opened the first Second City show in 1951 on a terribly cold winter night with a little ditty “Everyone’s in the Know but Me…”

It made me laugh, listening to this sweet tune and picturing her on the East River with Lerner’s helicopter coming down to whisk her away to his yacht. It was, for Broadway, if not entertainment, about as successful as one could get. That must have made her laugh somewhere. She dealt with mental health issues her whole life, and here she is, suddenly, the star, the genius, even.

And this genius inspired a musical comedy about a psychic who can make flowers grow with her voice. As the “inept” Daisy Gamble, she goes to a hypnotherapist to quit smoking. And it’s… Yves Montand though he ended up leaving the show. Under hypnosis, she regresses to a past self, and this transformation of self was nothing short of “astonishing.” He ends up falling in love with her past self.

Harris is almost a magical creature, which proved to reappear thematically in her press clippings, at least in the beginning, someone who inspired a particular direction of thought. “There’s more to us than surgeons can remove,” taking a line from the musical, so she’s mysterious — what she’s doing is mysterious. It seemed to be part of the intrigue.

“You’re not watching someone become the role, you’re watching someone become someone else,” Arthur Kopit said, the esteemed playwright of Oh Dad.

“This is not Daniel-Day-Lewis. It’s Barbara Harris.”

Austin Pendleton thought about it in his dressing room.

"Hm, how do I write a musical for Barbara Harris? Oh, I know, I’ll give her ESP and she’s reincarnated.”

He could follow that. He smiled. Makes sense.

The first night that I sat down with Harris in Scottsdale, Arizona, she was forthright about how much she tried to back out of it.

“When you tell them I can’t do it and they say never mind that and they give you 60,000 dollars to wait….”

She kept trying to quit.

Harris went to see Cinderella, a Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, as research. Pendleton said, in the Oh Dad dressing room, that Harris didn’t even really know who they were, and her face, all these years later, remarking this Cinderella hitting her mark, the lights, in a ballgown? Hilarious. Impressed doesn’t even begin to describe it. She had to leave the theater — “I can’t do that!” She liked Camelot, though.

“Is she for real?” That was the press’ question.

Meaning, her persona, from what I gathered, was a touch unbelievable.

“If you draw back the curtain, this I am certain, you’ll be impressed with you…”

The “unknown” within her even became touching and inspiring as Lerner wrote the words for her to sing in On a Clear Day You Can See Forever, a musical about a woman who harbors secret talents and doesn’t know it.

And “the little peanut” blew everyone away.

When I listen to her sing, I have to laugh. She said she couldn’t sing, and she really could.

“TALK to FLOWers right here….”

Tapping my foot, feeling a little foolish, the music captures her enchantingly offbeat but on-beat skip. She had an uncanny ability, according to Mary Martin or Peter Pan, “to make it seem like she was making up the lines as she was going along.”

The hypnotherapist wants her to show him what she can do.

“You haven’t got a thing to fear…”

Make flowers grow with her voice.

Think about Lerner, mostly, writing this musical about her…who tries to keep backing out, who keeps saying she can’t sing…

“OH kay…”

She pronounces her nervousness and growing acquiescence by opening the vowels.

“Just please…turn around,” she trips over the words. “Turn, turn, turn around…”

This is her other signature quality: vulnerability. And it was funny. It could be. It was her comedic brand, even, for lack of a better word, but then, Barbara Harris was undoubtedly commercial for being the improv queen with these unusual qualities. She’s a clown — another word that followed her throughout her career —a comedian though not a stand-up. She’s a character actress, but apparently, it wasn’t that simple. She literally appeared, from what I understand, as if she were changing personhood before your very eyes, even when she stepped offstage. She was the meeting of mystery and comedy.

“Sort of haunted, haunting,” Austin Pendleton said.

In other words, Harris could have starred in The Adams Family? As the one dressed in pink? Since Mike Nichols, a man who needs no introduction, described her as radiating that color. And she starred in “Hitchcock Presents” as well as Hitchcock’s Family Plot alongside Bruce Dern.

Maybe Beetlejuice? I’m not sure if that’s totally right, but she could exist in a Tim Burton film that meets Pleasantville. She’s not Winona Ryder, at all, but she could have played her role in Edward Scissorhands, I suppose, to then appear Park Posey style in Superman. I’m trying to place her within a more contemporary framework of references, given that she’s on that level. Maybe she could have been an X-Men, also, you know. Barbara Harris. Or, one of the children in the oracle’s waiting room in The Matrix. She’s bending spoons somehow with her consciousness. Lerner would laugh at that, I think.

She had a mental illness, and it turned out it was really genius.

She famously turned down A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, she was offered every role on Broadway at the time, just everything, and she turned most of it down. I heard theories about why: the influence of Paul Sills and the reticence that many of the original Second City members had towards their commercial success. Everyone I spoke to said that she couldn’t get over Paul Sills, because she couldn’t change her name after the divorce, which might have meant — she just couldn’t figure it out — but opening the fridge at AJs to tell me, as I’m reading her pick-up lines, she told him to get the girl! She told him to get the girl. Meaning, his future wife.

There’s a snapshot.

“Misunderstood,” she said, she felt misunderstood.

She could star as Jennifer Lawrence, even, opposite Tom Cruise in a zany and thrillingly real Mission Impossible. Here’s Barbara Harris — finding out she’s wrapped up in spies, and Cruise has to get her to safety. It would be a riot, a showstopper, Cruise in a crazy car with Harris trying to get off the cuffs. She could be a Jason Bourne, also. Someone who wakes up and knows nothing except that she’s a lethal weapon, she’s coming to discover, and it would be hilarious as well as art.

She can play psychologically complex roles — a woman with real range.

Harris in a life or death situation could become Oscar-worthy, even — picture No Country for Old Men, the scene in which Javier Bardem is about to kill that almost pure woman. Harris would knock a monologue like that right out of the park. Imagine an SNL actor becoming a Meryl Streep, you see. Jim Carrey. He’s known for his transformations — he became “the mask” itself. She’s considered one of the best in that arena.

“Hey Barbara,” Mike Nichols wondered, “why don’t I cast you in The Apple Tree?”

“I don’t know…” She said.

Natalie Wood was photographed with her mouth agape next to Barbara Harris as a chimney sweep. She captured everyone’s heart as a soot-covered ragamuffin in a muumuu who had only one wish, superbly off-key, with a sneeze: to be a glamorous movie star. She’s like a lost puppy, “rar rar rar…” on a sparse, cardboard set hand done with her brush. It’s hilarious and heartwarming.

In The Apple Tree, once again, we’re seeing Barbara Harris become other people over three acts which culminates in this Cinderella act. In a fit of magic, Harris transforms into a ravishing, radiant movie star with breasts that even she’s taken with. “I am gorgeous!” She says, brash. No sooner did she win a Tony Award, however, did she try to hand it to Rita Hayworth’s daughter. “You’re beautiful, you take it.” If there was a role that she didn’t want to play, it seemed, it was that of the glamorous actress.

This night, her behavior, sent waves through the press.

“Will success wreck Barbara Harris?”

Here’s another side of Barbara Harris — that doesn’t make sense to the media — spinning in a graphic of pictures of her in the shape of a question mark. She seemed to be many people but what that meant offstage would cast a shadow across her stardom. Her boyfriend, Warren Beatty, also broke up with her hours before she accepted the award, which might have shaken her. Why at this time?

“Her appearance was the perfect disguise for a celebrity,” according to Stephen Birmingham, a journalist who watched her on the set of Oh Dad. She was the total opposite of what one would think a famous actress would dress like, be like. I didn’t understand that, personally, though that’s true, I guess. She was anti-glamour, the ultimate “not in it for the fame,” which is what everyone wants to hear and doesn’t believe at the same time. “She loved being famous; no, no, she really didn’t.” At the height of her success, however, Harris began to disappear.

The curtain went down in the middle of the show the night after she won a Tony Award for Best Actress.

“Feelings are tumbling over feelings,” she was singing.

“Feelings I do not understand. And I am more than slightly worried. That they are getting out of hand.”

That might have reflected her reality a touch too closely for her, and I have to admit, I can laugh, at these moments, partially because it’s a touch too perfect, too. She can’t help but reveal herself.

“The baby-face look hides the fact that Barbara Harris is (sometimes) the Hud (the man with the barbed-wire soul). In a switch-blade street fight between Barbara Harris and Vietnam’s own Madame Nhu, the smart money would be on Harris…”

Her stunning vulnerability translated to a stunning impenetrability offstage, on behalf of the press, but I got the impression that it extended slightly beyond that, though she had close relationships with The Second City crew.

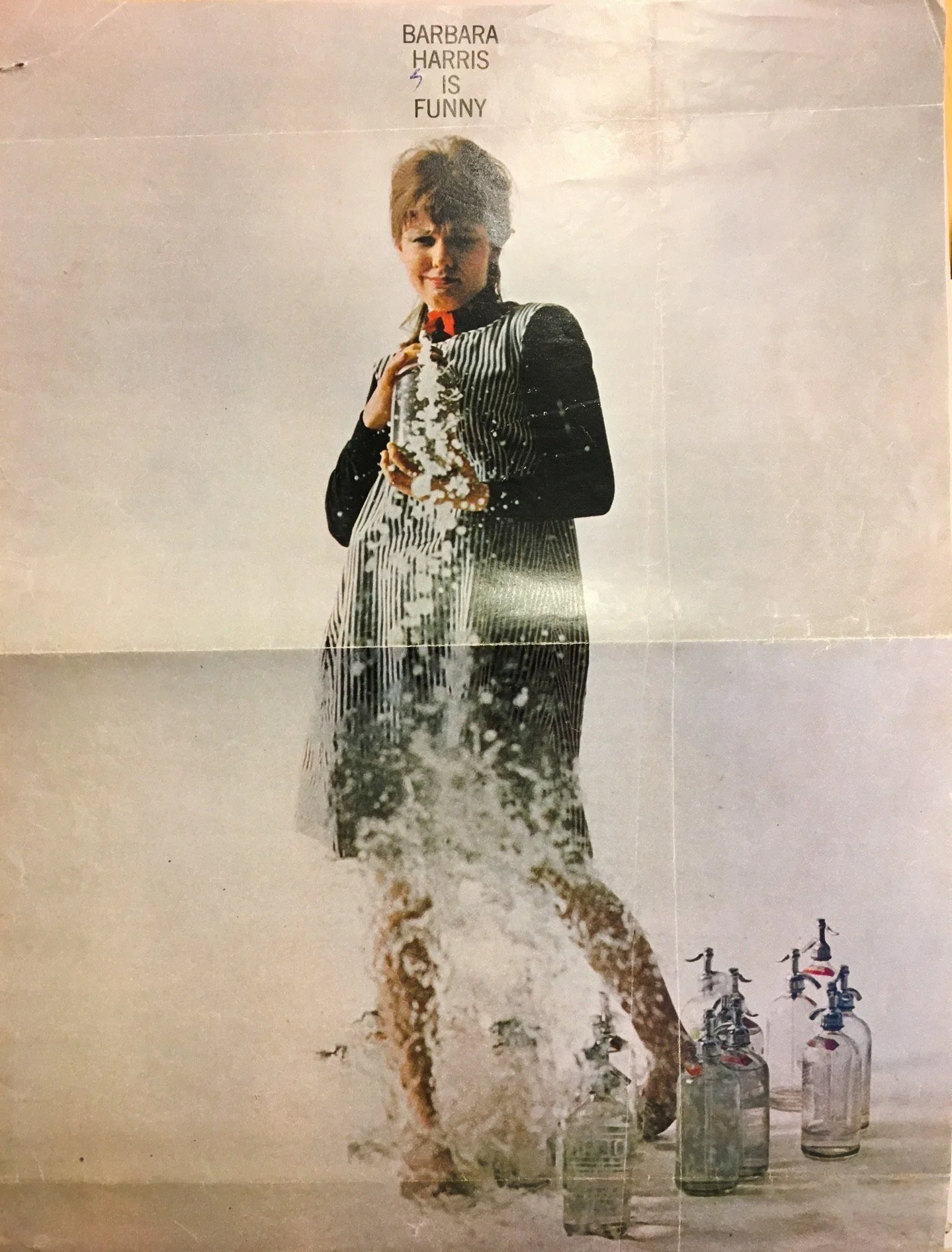

Barbara Harris in Family Plot

I did experience Barbara Harris to be a ninja. I did. She’s a street fighter, excuse me, in “a world that frequently terrified her,” Jeffrey Sweet said. She could disappear in the middle of a show. I only heard about one occasion though, and I’m like a scalpel when it comes to what I can point to exactly, so did they really have to lock her in the theater to ensure that she wouldn’t leave? Kopit even called her “boring” and “dangerously real” or “unreal” as a person whereas she dazzled on stage for the same reasons. Another journalist, I guess she was trying, compared her relationship to her fame with a lollipop, so her behavior appeared childlike, a woman who also could make “Lolita a credible novel.”

Though she backed away from the limelight, she was nominated for an Academy Award for one scene in Who is Harry Kellerman and Why is He Saying Those Awful Things About Me? from 1971. She auditions for Dustin Hoffman and gets cut off on her thirty-fourth birthday, it turns out.

“Playing the clown…trying to drown…”

She sings.

I laughed.

“Thanks,” they say, “you can stop now.”

But Barbara Harris can’t seem “to let go of this lamp right now” beside her on stage. No worries, she says, “you go on ahead.” These unusual, emotionally charged but seemingly unaware responses are so her, so brilliant. They show the internal life of a character artfully, even, if you think of the humor in it. It’s not totally realistic, either, but it is. She’s existing with the elements involved.

Is she serious? Is she…?

Exactly.

“We’ve got a real crazy” on our hands, Hoffman’s colleague whispers, but he decides to approach her. Tells her to take her time. Sort of taken with her. And she proceeds to deliver this ten-minute monologue, a shining example of her vulnerability, mystery, and humor.

“I got three good notes and I never seem to get to them…”

She doesn’t appear to have an agenda. She’s not giving this monologue because she’s trying to change the outcome of the audition, but it’s an Academy Award-nominated scene. The camera just sticks to her. It’s just her face, and across it different ages flash, her eyes mesmerizing dark. She’s 34, not 22, and she still can’t get the part. A fascinating woman for “the unique blend” of notes that she’s striking. There’s a quality to her innocence, even, that isn’t necessarily light.

Her fellow Second City mate, Severn Darden, said that “the reality of the stage was real” for Barbara. She didn’t break character, in other words, and here she is— on stage but not. It’s endearing but not simple. Bare. It’s her interest: vulnerability, a gift and curse? The line “do you like opera?” is my favorite. Was that sincere? Or was that Harris flashing a little of the performance of vulnerability? Is she using some of this vulnerability to reel Hoffman in? And this deep yearning for intimacy is so honest and human.

I asked her.

“Did you write that?”

The sunlight, almost at its peak, pierced through her black front gate, so she was covered in stars.

She could almost fool one into thinking that as Mary Martin said, but I wondered about that one.

She said “no,” but Jeffrey Sweet told me later that she did. She recited it to Herb Gardner, the screenwriter, in the middle of the night. I don’t think many know that she wrote it, intuited it, and it doesn’t surprise me that she said that she didn’t.

“Time mister,” she says, “it’s not a thief. It’s an embezzler staying up nights, juggling the books so you don’t notice anything missing when you wake up.”

And what happened to it? She asks. The time.

She was nominated for a Golden Globe for her performance in Robert Altman’s Nashville too, an iconic if not a seminal film. In AJs supermarket in Scottsdale, I saw that movie appear in the atmosphere before she mentioned it. It makes sense. Altman blurred the line between real and fictitious life purposely and presciently. The actors had to stay in character the whole time because they didn’t know when the camera would turn to them. Script? Loose guideline. Character? Bring in your real self. Politician, performer, assassin—this is fame; the lines aren’t clear, but Barbara Harris, regardless, sings the final number as the “crazy, really crazy” Albuquerque who wants to make it big, again. “It Don’t Worry Me…” She even wrote a song with Shel Silverstein that didn’t make it into the movie because it was “too good.” I had to laugh — was that part of it? Coupled with the characters she played and the trouble she had, maybe, accepting that about herself? I don’t know.

I don’t know what to say about her mental health problems, or what it means to be “beloved and that was part of the problem.” Someone told me that. Does that make sense? She struggled her whole life. Craig Lucas, one of the most distinguished playwrights of this generation, came outta the gate so generously to talk to me because she was that amazing and eccentric. It was known.

She was in a production in Chicago of Prelude to a Kiss. He said something like — this was later on in her life—” it was as if you were watching someone on a tightrope, and the whole set could fall to reveal it was all illusion, delusion.” So let’s take that impression and weave in the real mental health problems that she was dealing with. Less from the perspective that she had them, but more so that she was told since she was a young girl that something was wrong with her — times have changed — to discover she’s a genius? That had to be somewhat shocking.

An admirer of hers messaged me recently and wanted to know why she was so fragile and sad and why did she disappear from acting? The word fragile again. She was “a rare, delicate talent,” someone corrected. She was a force, also, truly. Her fragility was part of the appeal though. And yet, today, vulnerability is a sign of strength, so, I believe, that reveals something deeper about “us,” the public.

When she first came to my attention — I couldn’t believe that I hadn’t heard of her or that “no one remembered her,” but Pendleton said she was trying to disappear in 1963. So when the person who introduced me to her said that no one remembered her because of our “cultural amnesia…” I wasn’t sure how to take that though it was thought-provoking. He was referencing Jean Baudrillard’s America, which becomes funny as a book in my hand because Barbara Harris was in the desert. It became his central metaphor for American culture. What happens to a country without real roots in history?

“Driving,” he said, “a spectacular form of amnesia,” and we did — through the desert — in this story about connection. Meeting in some consumerist oasis at sunset. The two of us in oceanic parking lots— dry as a bone—which at night became as large and think and black as universe. As if we were the only two people in it. To me, that speaks to her sensuality as well. She was stirring for that reason I found. Someone who had “inspirational” energy around her, which might have inspired a fair amount of projection. Just because she was so young when she first developed “mental health” problems which remain vaguer than vague — I can’t even tell you what “she had.” And as a clown, as I studied it, from a psychological perspective, there is an unknown and it’s larger than the known — which is totally disregarded in western psychology. Meaning, I believe she could have worked through these problems. And I got confused in these clippings, in my interviews, like, wait, “who gives a shit? If she doesn’t break character?” Jim Carrey doesn’t. Sure, Mads might get annoyed, but he’s not going to make a “to-do” about it. “Who gives a shit if she doesn’t LOOK like a glamorous star?” Seriously speaking.

Just beautiful — the inky nights we spent crossing an ocean called a parking lot under the stars. I found myself at the pool in my condo…and why the pool? I sat down… again, why does the pool that glows in the night in a condominium complex feel like the most perfect setting to reflect on belonging?Since she threw me with her life statement, it would turn out: “confidence comes from belonging.” At the pool. Why the pool? Under an Inky night, no one around. Famously, she didn’t open her mouth for a while when she first arrived at the Chinese restaurant that the original members of The Second City lived and worked in, so when she did, at the end of a daily exercise, the room went silent. They figured she was never going to talk, and she had to give the moral of the story this time.

“Love is the key that opens every door.”

Mike Nichols laughed.

“That’s Barbara.”

She didn’t understand what was so funny about it, and she didn’t know, in general, why people laughed at her.

I asked her what gave her the confidence to do it then — start talking. Literally.

“Confidence comes from belonging,” she said.

It was even written on a note tacked to a bulletin board in her bedroom where we ate sushi and Chobani on a sleeping bag on her bed. We were watching an episode of SUV about a schizophrenic on trial for murder. At the end of this intimate scene, I noticed it. She felt that was very true…as commercials about pharmaceuticals droned on…with their hilarious side-effect warnings. You laugh, something in you breaks, and I asked a shaman what belonging had to do with mental health, and he said everything.

On her porch, a lingering chinoiserie in the corner, we floated in space in the silence stargazing, a couple of cicadas chit-chatting on the brink of summer; a snapshot, I told her, one hundred years in the past. The past exists then according to the night sky where we wish upon a star makes no difference who we are. It takes that long for the stars, twinkling, to reach us where we might hang our hat, too, at the end of the day before the last breath casts us out, back into that glittering canopy. History, connection — it was written in the stars. So thank you for “the time, mister, the time,” for yours and mine, a moment we spent some, valuable, together. Never forgotten.

Coming soon: excerpts below: