Barbara Harris took me to AJs SUPERMARKET to discuss the home and body section and it was genius

5611 Words

Standing at the precipice of AJ supermarket, Barbara Harris had summoned me to come—at once. “You have to see this place, you’re never going to believe it. It’s outrageous!” SUVs pulled into the parking lot. Beep beep, trunks opened, groceries went in. Ponytails swung with juice. Seniors turned the paper. Off the squeaky-clean cars, the sun reflected the paparazzi's flashing lights. I peered through the families and brown-paper bags on a bright, sunny day for the “Where’s Waldo” of Scottsdale, Arizona.

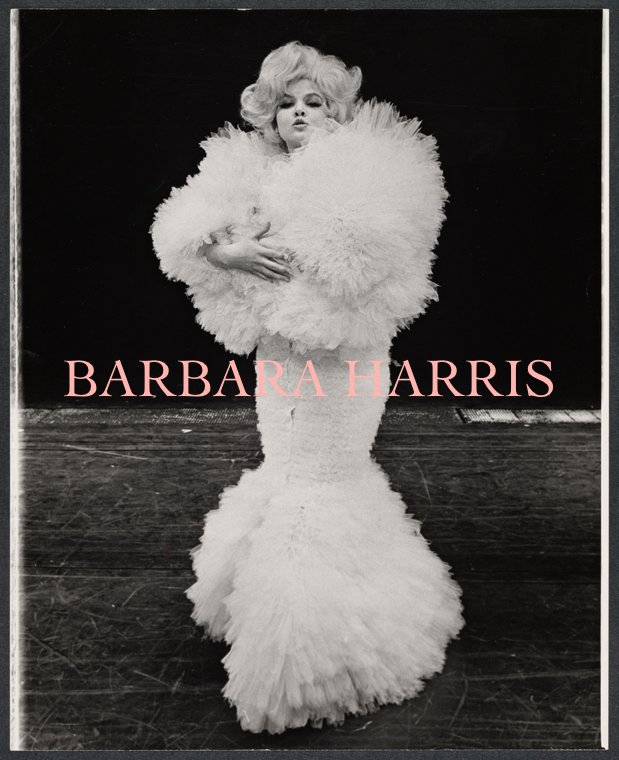

In 1961, Barbara Harris took a direct flight to the top when she stepped onto the Broadway stage in New York City with The Second City and dished out “mad characters faster than Christmas cookies.” She was nominated for a Tony Award for skits and sketches, not even a play. In the audience one night, Richard Rodgers, as in Rodgers and Hammerstein, then suggested to Alan Jay Lerner, as in My Fair Lady, that they compose their first musical around her as they both lost their respective partners. After watching her, a Marilyn Monroe comedian, seduce a nervous wreck of a man-child played by Austin Pendleton in Arthur Kopit’s macabre comedy Oh Dad, Poor Dad, Mama’s Hung You in the Closet and I’m Feeling So Sad, they hired her on the spot to be their inspiration, forget actress, now rummaging through her beat-up but won’t-give-up Honda Civic—all doors open.

“On a clear day…rise and look around you…and you’ll see who you are…”

The iconic, if not eternal, song was written for her. Barbara Streisand starred in the movie; Harris didn’t want to. And in the couple hours that we had already spent in each other’s company the night before, and it became poetic over these four days, we crossed oceanic parking lots dry as a bone that at night became the universe. The inspiration behind the unique and beautiful musical On a Clear Day You Can See Forever possessed that kind of limitless range in her bright eyes that could turn deep and dark. Barbara Harris was inherently mysterious, as she exquisitely and unforgettably exemplified in her Academy-nominated monologue in the film starring Dustin Hoffman, Who’s Harry Kellerman and Why is he Saying those Awful Things about Me. Her eyes are so black; they’re a massive unknown. Hard to pin down Barbara Harris.

Bent into the passenger side of the car, she looked different, headed for the backseat, plumper, eight-three, in Christmas red velvet leggings, a grey polo shirt, a Prada fisherman hat with red trim, and very large cataract sunglasses. Her rouged lips were still pinched and Puckish, sometimes. Her hair stick-straight and long was a departure from the short, spunky style she sported for most of her career. Waldo’s cousin.

That’s the thing, I pictured the “Where’s Barbara Harris?” version of that beloved book becoming a wild success somehow, even today, because it’s Barbara Harris, someone who doesn’t quite fit in but can play anyone, so she’d hand people hotdogs over here, appear over someone’s shoulder in a blond wig over there, play guitar on a grassy knoll back there. Heartwarming.

As the archetype of clown followed her career, I spoke to Bernie Collins about the subject, a world-renown clown, scholar, and fellow graduate of the Jacques Lecoq School in Paris, better known as the “clown school” that Zach Galifianakis failed out of in the TV show Baskets. “Clowns are found in every society throughout history except Totalitarian regimes,” Collins said. Political theorist Hannah Arendt attributed the break from belonging to the rise of that government, so clowns represent belonging as an outsider. Harris said that she could relate to that on the phone, “clown,” which, to her, meant something more like “misunderstood.”

Her color was pink, according to Second City colleague Mike Nichols, also the statuesque director of The Graduate. But she was “sort of haunting, haunted, yeah,” as veteran actor Austin Pendleton put it. She could have been in The Addams Family as “the pink one” at her boudoir then. It would have been hilarious, brilliant, should have been done. Already a “piquant” combination, “a unique blend of qualities” as a comedian, first and foremost, her arrival in New York in 1961 produced a magical effect— Bruce Springsteen playing from an SUV— a flare, a cosmic explosion: chemistry. She was the fastest-rising star at the turn of the 1960s.

Barbara Harris, right at the entrance, was quick on the draw.

“Hello! What kind of car is that?”

“It’s a Cooper.”

“What’s the paint?”

“I think the real kind.”

“In a switch-blade street fight between Barbara Harris and Vietnam’s own Madame Nhu, the smart money would be on Harris…” a journalist wrote. Closing all the car doors with conviction. “You’re going to see how ‘un-simple’ this place is,” she said. “First of all, they’re so seductive. They want you to buy everything before you get into the store. It’s outrageous.”

She dazzled New York in 1961 with that quickness, dishing out those characters like batches of cookies. I did find Barbara Harris to be a ninja, that’s the thing. She could have starred in Street Fighter and gotten nominated for an Academy Award somehow. She was funny, that’s the point, made these sorts of sentences believable on some level; she was slated to be the Meryl Streep of her generation as a comedian fundamentally. You know, someone who ends up enrapturing Rodgers and Lerner in the span of one performance in Oh Dad as a Marilyn Monroe meets SNL meets high art, kicking a dead body out of the way in a nightie — who’s this? — and no one knows if she can even sing, and then, she blows everyone away, and she’s clueless as to why.

The doors opened. The supermarket was glacially chilly. The slick raw-chicken-colored linoleum floor shone. Barbara Harris opened the first The Second City show on a blisteringly cold night in 1959 with a ditty. It couldn’t have summed her up more accurately or tenderly, or so the story goes. “Everybody’s in the Know but Me.” Little did that iconic group know they would spawn Saturday Night Live. I was standing beside a pioneer of the art form known as improv, one of the original members of The Second City, theater history. Her limbs extended towards the scene before us as if it spoke for itself. Beep…beep…beepbeepbeep…from checkout.

“Easter is coming,” I said. Peeps.

“Doesn’t matter what’s coming,” she said, “it’s always like this.”

“Do you want a bunny basket? Look at these flowers—wow!”

“I know…”

Merging into the store before the store, “We got candles…”

“Nightgowns…”

“Pineapple paraphernalia, aprons, we got shawls, we got everything here…” butterflies.

Paul Sills, the first director of The Second City, defined improv as “a kind of confrontation with the unknown.” I surrendered to the exercise. I didn’t have to know where this was going. We had time. I took her lead. Getting to know you.

“Yeah,” she said.

“We got more pouches!”

Raising her hands, she sort of took the space. I’ll never forget it. “If you have a lot of money and you…” as if she handed it to me at AJs Supermarket.

“Don’t want to go anywhere else…”

She paused as someone who doesn’t just pause. This was a reveal, a state. An actress. Maybe teacher. “You can just shop here,” she said, just like that, as if she were instructing me. “Just what you need,” she meant it. “All of this is very important.” She continued.

Oh, I thought, it doesn’t have to be LOL all the time.

Austin Pendleton, framed in the bulbs of his dressing table, communicated with such present feeling the first time the door opened to the legendary rehearsal room for Oh Dad in 1961. “And there she was,” the talk of the town, the improv queen soon to be Broadway star, with director Jerome Robbins (Fiddler on the Roof) and William Daniels, Assistant Director. He said her “fluidity” made her a rock onstage; she was a real guide. I just got a taste of it.

Violà Spolin founded improv based on the idea of “not knowing,” which aimed to free the person from the need to be funny, good, or free from intellectual constraints that stifle creativity. A character would spontaneously emerge from the circumstances of the scene—without props, script, or rehearsal. It turned out she was quite gifted at that.

“Crabtree and Evelyn, always,” I said. “You can’t have a store like this without Crabtree and Evelyn.” “True,” she admitted. “Sleeping over at other people’s houses,” she brushed over. “It’s just stuff. Nothing but stuff. Stuff stuff stuff.” Her seemingly out-of-place comment corresponded to the image that came to my mind of a bathroom once upon a time.

“Unicorns, Buddha, trash cans…”

“It’s not exactly feng-shui.”

A fascinating, spooky exercise, improv; players can connect, sync up, and even access information. I had read about a doctor who ran backstage one night to ask an improver if he had gone to medical school because it would be impossible if he hadn’t. That says a lot about the mysterious nature of improv, “how are you doing this?” To add another layer, story-wise, on stage, I could drop mask here as the image held deeper significance for my character emerging from the circumstances of the scene. I sort of learned something about dramatic writing, at least from the position of an actor. We reveal ourselves over time, despite ourselves. And it was amazing that the time I spent with her, coincidentally, situationally, gave me an access point as we were just getting to know one another. I wasn’t concerned about asking her questions. In fact, I couldn’t imagine that interfacing with fame was always easy, for real, speaking of “reality.”

“Wow it just keeps going.”

“Hard to believe it.”

Harris masterminded “The People Scene” at The Second City, which is grounded in character and story development, where the humor, or play, comes out of vulnerability. And it would become her shining jewel as an artist in a field of masks.

In “First Affair,” one of the most iconic scenes in improv history, Barbara Harris confesses to her father, played by Severn Darden, that she engaged in her first sexual affair, a vulnerable situation for both parties. I adopted that as an approach in exploring this exchange with her because she was, as an interviewee and star who was also “ill.” She was feeling me out. I was on her side. I didn’t find her reticence to fame that outrageous. She hated interviews and this aspect of her career, but she agreed to meet me.

“Of course these handbags are very…”

“Yeah. Panda handbags.”

“Necessary,” Barbara Harris said. “The big one is really necessary.”

She said something about stealing it, and you see, these sorts of questions were the most honest and enjoyable, for me, to ask as she’s an improv master.

“But if you were going to steal a bag, why would you steal a panda handbag?”

“It belongs to like a child who has like 100 dollars in there.”

Later, hanging off a rack, I read a t-shirt, “she who sleeps with dogs…?”

“Wakes up with fleas,” she shrugged, “something like that.” I laughed.

Scottsdale, a ritzy town, I supposed, with these price tags, but then, it had range, I could tell, and she’s a Great Depression baby. My father was ten years older than Harris, even if I was born in 1985, which was one of the reasons why I was here. This section would appear absolutely outrageous to someone from that generation. A reader today might not be aware of that history anymore speaking of America, the book by Jean Baudrillard that someone gave me thinking about why she disappeared and why no one remembered her. As he drove for miles, the desert became the central metaphor for American culture, a spectacular form of amnesia. We were in the middle of one. To that, Pendleton replied, “she was trying to disappear in 1962.”

“What are those things?”

Her shocked face, unforgettable, “crosses? They have crosses?”

A long string of giant wooden crosses.

“Do you wear them?”

“I assume so! You don’t want to price tag though, or no,” she thought, “you leave the price tag on. Must leave the price tag on.”

“I believe in transparent government,” I said, and I could change my mind.

“No, you don’t wear them.”

“Yah!”

“I mean, if you were a giant…”

“You have to be a very wealthy Christian.”

“Pious…”

“I’ve never seen anything like that!”

Mary Martin better known as Peter Pan—a line that gets blurred when it comes to actors to introduce how fiction and real life can get muddled— said that Barbara Harris had “an uncanny ability to make it seem like she was making up the lines as she went along.” She even fooled me into thinking that she hadn’t been to AJs before, so what did she know, what didn’t she know? A real question with her.

“I think it’s decorative…”

“Noooo!”

At the “next time you need something from me, reconsider” magnet, I needed to take a snapshot. Harris laughed, which was rare. Along with being considered a true genius; and it makes me laugh because everyone is (not to say that she isn’t, but to take the pressure off), she was mentally ill, or so the story goes.

“What does that mean?”

“I don’t know, I don’t know. I don’t know what any of this means.”

“Here is Paris!” Barbara Harris.

“Of course, you can never ever…”

“Paris on your door…”

In the beginning, as I was reading through her press clippings at Lincoln Center Archives, I tossed some of the ideas swirling around her in the early phase of her career out to people I knew. “Innocent to her own talent, didn’t want to be famous.” I winced. “Don’t buy it.” Suddenly confronting that phrase in this setting. We validate beliefs with our purchasing power in a strange twist on indulgences, the Catholic Church’s ticket to heaven.

Into the clever towels section, the two of us surrounded by a spectacular display (!) of ironic witty phrases that excuse alcoholism, I don’t understand in this world, what’s genuine and what isn’t sometimes. People didn’t “buy her.”

“I need a drink,” she read. “Very important.”

Within eight months of arriving in New York in 1961, she was a downtown smash hit, would be nominated for an Obie and Tony, and inspire two of the biggest composers. I don’t think Barbara Harris ever thought that she would be that person, which makes her all the more inspiring, and so what? She couldn’t believe it. The actress playing Cinderella, as she had dashed to see a musical suddenly signed to inspire one, hit her light in a gown. “I can’t do that!” She had to leave the theater. “On a clear day…”

“Will trade husband for wine… you gotta iron these towels of course.”

“I know someone who buys this sort of thing.”

“Is it funny?”

Now, if you’re really that addicted to alcohol, you’ve got a problem. If you inhabit an unreal space, it’s funny. We live in unreality, as a world, ourselves. Reality turns out to be a complex exercise where people seem to be able to clearly delineate between these areas: joke, fantasy, or they don’t. The world is ill, too, skates into unreal territory that’s “kinda true.” Realities can bleed into one another. No one would disagree.

“They sell this crap…”

“People like this crap.”

“This pen is very important.”

“Ann Tantor.”

“What does that mean?”

“I think it’s her name, and it’s her pen,” I said.

“I guess so…”

She couldn’t even talk when she got to the abandoned Chinese restaurant where the future Second City lived and rehearsed fresh out of high school with a diagnosis already. I had asked her the night before what gave her the confidence to do it because I couldn’t, and it was the first time in my life that I admitted it. I didn’t put that on her, but my question came from a real place. That’s what I mean. I could enter this situation with enough reality, truth, so I could think about what it means to be vulnerable from a real place as that was her gift onstage.

“Confidence comes from belonging,” she said. I didn’t get it, honestly.

Elfin-face. Doll face. Curtain of bangs. Bambi-eyes. Button-nose. Cherub cheeks that cry out for pinching. To the bewilderment of many, she exuded a womanly intuitiveness, an adolescent awkwardness, and the innocence of a baby, which made the “real” Barbara Harris ever more mysterious. “She might be descended from the elves, or perhaps before coming to New York she lived under a bridge with her uncles, the trolls, or in a forest pool.” People could tell something was going on but these were the 60s. Her fluidness was discernable, her personality offstage became perplexing. Her look and style didn’t always make sense, so unglamorous, even, but she seemed to possess almost a supernatural gift.

“Yea! Atlas Obscura. Dunno what that’s about.”

“An Explorers Guide to the World’s Hidden Wonders…”

“Sandlewood.”

“Sandlewood?”

What is the self? Alan Jay Lerner seemed to be asking himself that question while composing a musical in the mid-sixties about a psychic who makes flowers grow with her voice and regresses to a past life under hypnosis. Her transformation from the bumbling smoker Daisy Gamble (she smoked) to the regal 18th-century British Melinda Wells in On a Clear Day You Can See Forever was heralded as nothing short of astonishing. Two-time Pulitzer Prize nominee Arthur Kopit even assured me, seriously speaking. “This is not Daniel Day-Lewis; she’s not becoming the role, she’s becoming someone else.” An astonishing statement.

“Pootin,” no way, I saw it. Someone said that reality sometimes scared her, and I understood why. “Of course you need a book to use a shower burst,” she said. “I do love this,” I said, “yeah,” she agreed. “These pop up cards.” “Those are wonderful, yeah.”

To many journalists, it didn’t appear that there was an actress there at all, something appeared to be doing this to her, literally speaking. Improv historian Jeffrey Sweet nodded. “She astonished Scottsdale, Arizona; she became sixteen.” In her sixties. Up against some crippling shyness, two entities seemed to be opposed in her. “Aisle one.”

“Then you get to chips,” she stood there, bags and bags of shiny shiny packaging. “Can’t get away from chips! Chips, all kinds, everywhere. It’s the worst thing in the world. I don’t…”

“Wanna taco about it…?” A towel.

We got to the food, finally, a long day’s journey into night — along the cutlets — “I’ll al co hol you later.” The Home and Body section curated…transitioning. Santa in view. “Is that for sale?” “This is the USA, everything is.” We made a left — to sushi. Cartless.

I didn’t interview anyone until after she died. Not everyone spoke about her like that, but what do you do with semi-unreal talk? I can’t type that without giving it real thought. People basically told me that she could have contributed to the field of psychology.

She was diagnosed quite young, too, with a mental illness to start winning everything and spawning supernatural musicals because she was an anomaly, a completely different human being, apparently, offstage, but I can’t ethically say it with certainty, though enough people communicated that she had moods and struggles and could even be “a fairy godmother.”

Cold rice and seaweed vaguely in the air, Barbara Harris realized that she had forgotten her credit card and her play about senility as women rolled raw fish and avocado. Between the sushi station and beer aisle lit up, she had to venture out of AJs to get cash or find her card. Through the plastic containers of bright brown black white crispy soft sugar cookies meringues macaroons biscuits — everything to be discovered, Baudrillard said, everything to be obliterated—she wanted to introduce me to Flappy, a stuffed baby elephant. A mass-produced homey smell lingered there…Barbara Harris pressed his little foot. We had settled at a café table, a deep dark roast in the air. “Do your ears flip flop…” they covered his eyes and vibrated. “Wow.” Harris did not break, she was a pro. I laughed, I laughed a lot. We analyzed the song lyrics, “what does this mean?” I asked. She did not know, emotionally, and disappeared into a shaft of sunlight — the doors sliding open — she wanted me to contemplate it.

“Do you use them as a blotter…”

About forty-five minutes later, I tried to shield her when she walked in and announced, “I have like a thousand dollars in here.” Fearful, that she had no money, generally, she called her bank on speaker phone to double-check. I plugged my ears and projected a “LA LA LA” cocoon around us so I wouldn’t hear. I wondered if that would surprise people, and I think it surprised her on some level. I tested it out on a friend later who asked why I hadn’t listened in, speaking of a line: public versus private, and how rare it is for someone to consider someone else’s boundaries. The world, too, you see, can contribute to a problem, not understanding how and why, for she swung, emotionally, and of course she would. She doesn’t know me. I could picture her later, “shoot,” making me laugh.

Reality happens between us, Viola Spolin said, something to remember in the age of “you create your own reality” that coincides with a crisis of belonging and connection. “Are you okay?” Wouldn’t that be the response? Between cheap cookies. She had money? She did. In a supermarket, even, I had thought about that question, “is nothing real anymore?” She did. She had money? She did. That’s all I cared about, really.

Nearing check-out, I had been mistaken however. Barbara Harris hadn’t simply wanted to investigate the outrageous Home and Body section, dissect the lyrics sung by Flappy, the stuffed baby elephant. In a miraculous coincidence known as perfect timing, the BEEP BEEP from check-out accentuated her lost open face, searching, beep beep, “I guess we better do the shopping now…” Beep… She shrugged. I imploded, I will admit.

Pushing her cart down aisle five catching the manmade so light so bright it shone between aluminum cans, Robert Altman appeared in the atmosphere as we headed for the pinto beans. Not a far stretch, I thought, Campbell’s soup disappearing behind her head. She starred in the seminal film of the 70s, Nashville (1971). We were nowhere near the subject though; I did not ask a question after the first night. I didn’t generate chatter, either. I was just there as we were feeling it out. But then, she mentioned it.

I wondered if she belonged to the “mysterious section of mental health” I keep hearing about. I.e., “sensitive people.” As a “genius who was ill,” she already does. I just don’t know what to do with either of those terms, but I didn’t think it was that farfetched.

She had an uncanny ability to pick up on things, read a situation, Mike Nichols said. Perceptive, very. I even trusted her perception. Jeffrey Sweet told me that she intuited the Academy Award-nominated monologue in Who is Harry Kellerman and Why is He Saying Those Awful Things about Me in the middle of the night. She denied it before he confirmed it. I wasn’t surprised, she’s “in the thing,” I imagine. But still, Harris got up off her pillow, “this isn’t right.” It’s just to say that her talent came with a fair amount of mystery attached.

Can anyone among us have an inkling or a clue what magic feats of wizardry and voodoo you can do?— On a Clear Day You Can See Forever.

I even told the people I interviewed that these four days were almost like a work of art, a piece in itself. No one expressed surprise that a moment spent with Barbara Harris could become art, which is astonishing in itself, and highlights a disconnect or the chance to become art by simply relating to her. And so, Robert Altman appeared in the atmosphere down aisle five.

The actors in Nashville didn’t know when the camera would turn to them; they had to stay in character the whole time. He wanted them to bring as much of themselves into the role as possible to crack through the fiction of film. “The unreality of the stage was real to Barbara,” Severn Darden said around the time that On a Clear Day debuted. She’d exit the stage for real to hang up a coat. It drove them crazy. Some actors don’t break character, but she could leave the theater in the middle of a performance, too, though. I don’t know how frequent an occurrence that was, so I’m not going to conflate a reality that I cannot confirm in the real. She did, all the same, skedaddle out the door, tried to escape the Entertainer of the Year awards, and even, I read, give her Tony Award away to Rita Hayworth’s daughter backstage.

Today, I thought, that just might go over well.

I could picture Altman panning over the edge of aisle five, the “bad boy of cinema,” nodding to him, even, slightly irreverent myself, “you can cut it,” cutlets behind him. Liking it, liking the pinto beans, “yeah, fame.” Make plans with cans.

He blurred these realities in Nashville as that movie is explicitly about fame. The two of us walked, between bright labels glued tighter than nature, through a world today in which everyone is famous. Social media democratized fame and blurred the private and public domains. We’re all brands, now, a commodity, a business, a message, in “the Supermarket.” Thinking about Baudrillard, who went in search of “Astral America.”

As I didn’t ask her any questions, when she took a step, I took another, just one, in a direction that genuinely interested me to keep my energy agendaless and super clear. I tried to be considerate of someone who might be sensitive, I don’t know; we already had a couple of syncing-up moments. Later, I realized that I was revealing myself, which was part of the exercise by nature of choosing honesty and vulnerability as an intention. I wanted to know about the songs, always, first. I had wanted to be a singer, once upon a time, did I know? No. What a dance: what know, what we don’t know. Pinto beans clanking into the cart, she wrote a song with Shel Silverstein, the legendary writer, for Nashville.

With a slight drawl, she sang it as she moved along. I kept myself slightly back out of respect.

“I don’t know how other girls do it, laughing and having a ball, maybe they’re trying, but

I’m out here dying, can’t figure out nothing out at all. Anyway,” she shrugged, “I’m going away, anywhere that I can. And anything I gotta do, I’ll do to get out from under where that I am. There might not be stars in my horoscope, There may not be stars in my eyes, but I gotta let go…”

“I got a one-way man…hm…I don’t know.” She shrugged. “She’s trying to leave him.”

She couldn’t remember it.

“It’s going to come to you,” I said.

“No, it isn’t.”

I forgot she was older for a second, so in this case, I wasn’t going to put on an act or cover-up because I felt uncomfortable or “bad.”

“Here’s the thing, I have the lyrics…”

“How?”

“In the Nashville book…” I leaned over the handle, if I am not mistaken.

As in Jan Stuart’s Nashville Chronicles: The Making of Robert Altman’s Masterpiece.

The song didn’t end up in the film. Altman thought it was “too good” of a song for her character Albuquerque to sing, a farmer’s wife who dreams of making it big as a singer in Nashville, but is the least likely to succeed, and by some miracle of luck, a murder, even, she gets the final number in the end after a music star is shot instead of the politician.

“They may say that I ain’t free…but it don’t worry me.”

Strange. Catchy. She’s the least likely to succeed, one of the recurring roles she played. But then, she had somewhere to go as a becomer. That kind of character is always inspiring. Who doesn’t have the potential to become…? In more ways than one. Nice to know…as we headed to pick up her Chobani. Opening up the refrigidaire, the cold cold air, I read her pick-up lines by the melons. “They say that?” She was, inspiring, beep — beep beep beep — because of who she was, who she played, the contrasts and similarities between them, but in the 1960s, she couldn’t be public about her “illness.”

Inches from checkout, she started checking over her shoulder: pharmacy.

Her friends knew, everyone knew, “You cannot talk about her without mentioning it.” But what am I mentioning? Who knows if she was properly diagnosed, on the right medications, had a real process for unbecoming if that’s what she’s doing supernaturally, or if she received the care that she needed. Her relative said that she came out of a traumatic childhood, which incites more empathy than mental health issues do. “Not like there’s anything wrong with that,” too, it’s the Seinfeld statement of our times. If I hadn’t had two families that were mentally ill, I wouldn’t be here. It took me a long time to hold my head up high though the British, especially, always remarked on my exquisite posture.

And here she is —an extraordinary actress who had “a lot of people inside of her…?” A Battalion of Barbaras; the title of the article when On a Clear Day You Can See Forever opened. She holds herself with a flower. Was it a multiple personality disorder? Offstage? I didn’t hear that term, to mention it, and yet she came from a formation that clearly defined it, so where’s the line in all this? A journalist went off about how stuck out in a crowd of female clowns because a pale rain cloud hangs over everything that she does. “She is funny, but it hurts to laugh.”

“You care about her,” Lerner said, as if all that, basically just means that.

She bewildered the press, playing solitaire for a journalist who came to “watch her on set” and was not self-aware, to flip it. And I can hear it, “genius,” the game of solitaire, oddly being watched in this setting though he doesn’t know that.

We got the sushi.

She was “the utter opposite of what you’d expect,” the most “unlike a star” anyone had ever seen, and isn’t that sort of refreshing? Pamela Anderson started a revolution and a new phase in her career because she doesn’t wear makeup. Two people in Scottsdale said she used to be famous; she’s an Academy Award nominee. Would you get over the fame point?

“On a clear day…”

I felt that, today, Barbara Harris would be embraced for the whole of her in a way that wasn’t possible back then since healing is even framed that way. Imagine, “actually,” Barbara Harris on the mic, “I’m just learning what my experience is.” Or “yeah,” she’d shrug, make you laugh, how she said it. She made me laugh later at how she alluded to it, “I feel like I’m lots of different people,” and that might be, funny enough, the most relatable statement she could make.

She was who she was, beloved. A truly gifted actress told quite young that she had mental problems. And at the end of her life—everybody has them. Reading Wellness sections, it’s crippling OCD here, seven distinct personalities over there. The world has changed, at least in some public corners. And people still don’t know what it means. Anne Hathaway recently played a bi-polar character, warning someone that sometimes she’s so terrible… but she isn’t afraid.

“Brave, brave, brave,” Paul Sands called her, a Second City colleague. Brave.

At check-out, I don’t know what to say about illness, if one always has to be, beepbeepbeep. I’m not even trying to say that anyone has to change, that there’s anything wrong with it. It's a confusing subject. And here’s Barbara Harris, Waldo’s cousin, someone in which Alan Jay Lerner saw forever, who has the power to become that book, you know? Eternal. Isn’t that something? Lerner, he really saw that. What a beautiful effect. The direction of thought, even, though I can imagine the “supernatural trick” might shock someone with a mental illness, and that people out today would understand. Gathering the plastic bags, she never even thought, couldn’t have even imagined that she was gifted, could be gifted, would spawn a musical. Isn’t that amazing about improv, originally founded to foster connections? To free a person, even, from the mental mind? And “the moral of the story is?”

She raised her hand in The Second City, finally, and it silenced the room; no one thought she ever would speak. “Love is the key that opens every door.” She was a touching person, who communicated indirectly, perhaps, but that’s not the word for it.

“Confidence comes from belonging,” she said. She felt a part of something as someone, to ground the reality of it, was diagnosed with a mental illness, and most people would be able to relate to that in a real way regardless. Brave. Vulnerability.

She’ll always be remembered and revered as one of the most unique, brilliant actresses that ever graced the Earth who, today, might, just might, be more significant and relevant because of the mental health journey that she had. This is Barbara Harris. Genius. On a clear day you can see forever. The two of us emerging from AJs, the camera panning over the parking lot and into that big blue sky… “I can’t do that!”

Onto Two Sister’s Consignment Store…